Rothko in Paris, Part 1

Mark Rothko (1903-1970) created artistically and emotionally powerful paintings. Although they were well received in his lifetime, it was only after his premature death that they began to receive the overwhelming admiration and respect and acceptance, even devotion, they are now widely given. In 2023-24 the largest gathering of Rothko paintings ever, 115 of them, was shown in a Paris retrospective at the Louis Vuitton Foundation (Fondation d'entreprise Louis-Vuitton) museum. It was a rare chance to see so many Rothkos, and the opportunity is not likely to occur ever again. Many are in the Tate Museum, which -- astoundingly -- lent them all to the Paris show. It is improbable the Tate will ever lend them all out again. And trying to see only all the non-Tate paintings would require extraordinary effort and travel. So, the Paris show was a once-in-a-lifetime event. We waited until the ski year was nearly over and saw the show only days before it closed.

First, a word about the museum and the display spaces. As we approached (and while we waited in line outside for our specified entry time), it wasn't obvious how such an organic, exuberant structure could be a comfortable site for viewing paintings. It is a markedly three-dimensional building. How would it display art that is ostensibly two-dimensional? Frank Gehry's design, and the entire LVMH foundation project as proposed, had been criticized, passionately and vigorously (it was Pais, after all), as an intrusion on the Bois de Boulogne and the neighborhood. Despite the objections, the museum was nonetheless built and it opened in 2014 (also despite allegedly massive cost overruns).

According to Wikipedia, there are 11 galleries of different sizes (although it seemed as we went from gallery to gallery there were more than 11, and even when we thought we were at the end we found two more galleries that held some of the latest and best works). The billowing exterior walls have been described variously, and most neutrally by Wikipedia, as taking "the form of a sailboat's sails inflated by the wind. These glass sails envelop the 'iceberg', a series of shapes with white, flowery terraces." In Gehry's defense, it is possible that site limitations forced structural design compromises. According to Wikipedia, "Gehry had to build within the square footage and two-story volume of a bowling alley that previously stood on the site; anything higher had to be glass." Although it is hard to consider sail-like glass walls that billow out from the central structure as much of a compromise, and certainly Gehry has never seemed to be much of an adherent to a "less is more" design philosophy.

But the building was undeniably striking, especially on a day when a mix of blue sky and white clouds reflected from the glass exterior panels.

Inside were the galleries holding Rothko's paintings in pretty much chronological order.

He painted figuratively early on. There were some examples, here a subway scene. There was even a landscape.

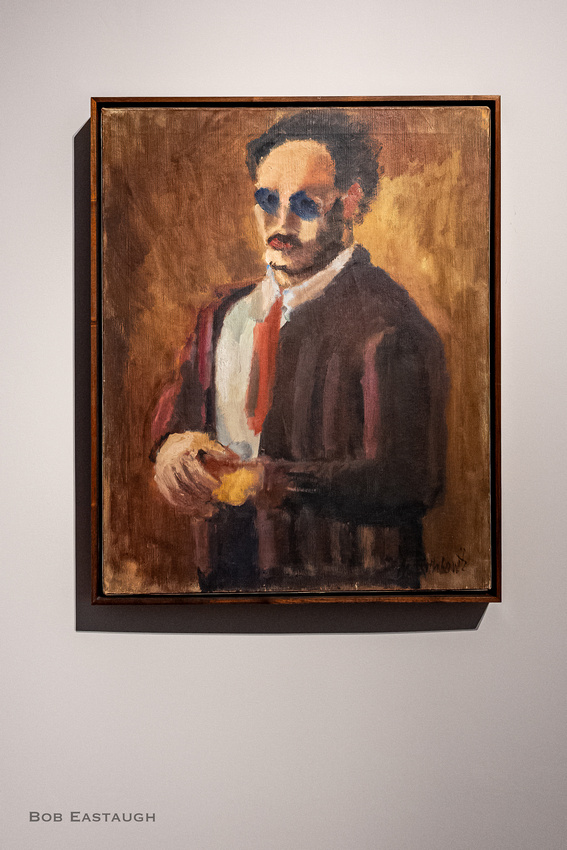

And this self portrait was figurative, if pretty abstract (and emotionally foreboding):

Although he had painted figuratively early on, Rothko became best known in his lifetime for his purely abstract expressions of color. But full recognition of his brilliance really came after his death. Even the broad public (witness the crowds at the sold-out retrospective) now recognizes his brilliance in creating large abstract works juxtaposing swathes and fields of color. Each of these fields was itself composed of complex accumulations and many layers. Even the dimensions of each field (and each painting) were complex, in the sense the "edges" and "borders" were ambiguous and hard to define; those terms are really misnomers when applied to these paintings. Even seen at farther-than-normal viewing distance (difficult at the retrospective, given the throngs viewing each painting), the fields retained their dense complexity, and their sizes and shapes retained their ambiguity. And the ambiguities of hue and value remained largely discernible even at a distance. The dominant color of a given field (green, or red, or yellow, or whatever) was striking, but didn't overpower the complicated constituent elements. Closer study (after threading around clusters of viewers) revealed more of the subtlety and ambiguity in each field. These are technically complex paintings.

Here is one sample, with a sample detail.

The result of seeing so many great paintings in such a short period of time (visits and viewing were time-limited) was sensory and mental overload. And regret, that we hadn't the time (the show was closing and sold out) to visit the paintings again or the foresight to have reserved a second day. It was overwhelming to see these great works, and so many of them. Any one of the 11 galleries, and probably individual paintings, would have justified hours of study and contemplation. The scale of some was itself overwhelming. The longest dimension for some was about ten feet. The next photo gives a sense of the physical context for "average-size" paintings in the show. Some (such as those originally painted for the Four Seasons) were even larger.

The display conditions were remarkable. As Rothko had intended, the ambient light in the galleries was dim. Rothko sought to make the paintings themselves sources of light and illumination, and his complex layering of paint (that he often mixed himself) was his means of producing work that, notwithstanding fields of predominant colors that were not inherently bright, did indeed seem luminous in the dim galleries, as though they were internally generating their own illumination.

Back now to the galleries and the abstract paintings. These were some of the earliest shown. Rothko had not yet achieved the structural simplicity that made the later paintings so much more powerful.

More to follow in the next post.

And this link takes you to my website gallery showing more (and larger) images of Rothko's paintings, and more of the museum.

https://bobeastaughimagery.zenfolio.com/p697865809