Realism and Photography; September 2017

From the beginning, one of the perceived virtues of photography was its ability to depict with exactitude the scene recorded; i.e., its unique ability to achieve "realism." This ability was seen as a virtue in part because it differentiated photography from the accepted arts, especially painting. (This ability was not universally admired; it was also seen as proving that photography was merely a mechanical - or chemical - craft that required only some technical skill, and no artistry.)

At any rate, the concept of "realism" in photography has always been hard to pin down. Even in early years technical pioneers were dodging and burning parts of prints, sandwiching negatives, tinting, double-exposing film and prints, and retouching. This sort of manipulation could be in service of enhancing "realism" (because it helped overcome photography's early technical limitations, such as limited dynamic range, and thus allowed a print to more closely depict what the human eye would have seen). But it could also be used to produce images that heavily changed reality. The best illustration was the skilled editing by the Soviets to add, or subtract, people who fell in and out of favor - sometimes terminally - from group photos of Party leaders. And at the opposite end of the spectrum, a few purists even insisted that merely cropping during printing was improper.

All this was back in film days. Now digital photography has made it possible for anyone to change anything. Need a moon? Just add one. Need a cloud added or subtracted? No problem. Is Aunt Sue, who was prominent in the group photo, now out of favor, but Cousin Jonah missed the shoot? No problem. Photojournalism and perhaps science (at least, for the moment) are the two remaining bastians that prohibit alterations. Photoshop is everywhere (even if few have mastered it). In popular culture, Photoshopping is synomous with changing reality. (Thus, when Ryan Gosling takes off his shirt in Crazy Stupid Love (2011), the audience laughs every time Emma Stone exclaims, "It's like you've been Photoshopped!")

Does this matter? What is reality in photography, especially in a society that seems less interested in truth and honesty?

But beyond that issue, there is a much more subtle question, raised by Susan Sontag. More on that later.

This digital photo of a Tour de France racer (David Millar) was edited in ways typical from film days: dodging to vignette the racer, severe cropping, and sepia toning.

This moon, silhouetted in Auke Bay, was a single image.

But this picture of a statue on the Charles Bridge in Prague actually combines two shots, one of a sharply focussed moon taken only a few minutes after the statue was photographed. (In effect, the sharp moon replaced the out-of-focus moon that was in the original exposure of the statue. The lens I used could not, at the required aperture, focus sharply on both the statue and the moon in the same exposure. Another way to achieve this effect would have been to use focus-stacking, which combines two or more images that were focussed differently. I sometimes use that method for still-lifes, such as flowers.)

This image of a dominant racer in the U16 Western Regional Championships was converted to B&W and then the tones were inverted.

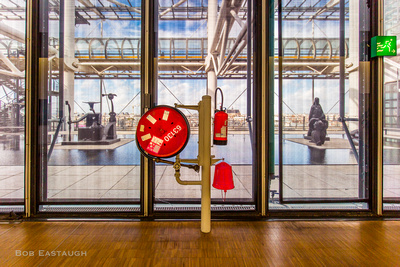

The colors were brightened and emphasized in the image of the fire standpipe in the Pompidou, to give it the same values and seeming importance as the "other" installations at the Pompidou.

These images all involve different degrees of strict realism in the sense that they did or did not display exactly what a human eye would have seen when the shutter was pressed.

Comments

After a lifetime of mainly expressing myself with words, my postings here will mainly rely on images. They will speak for themselves to some extent, but I'll usually add a few comments of explanation. I've taken photographs for decades, since the 1950's, inspired in part by my father's photographic skill. Four years of photo assignments and quality darkroom time eventually gave way to decades of casual and family picture-taking. I re-immersed myself when I left film and turned to digital.