Art for Art's Sake, and for Ours.

Art is a constant and fundamental aspect of human existence. We don’t need to define its exact boundaries; we simply need to acknowledge that humans produce it. And that they are collectively (if not individually) driven to produce it.

It is irrelevant that some humans may be indifferent to art or even consider it to be a worthless distraction, because the larger human community collectively appreciates art in concept. It is equally irrelevant that there can be disagreement about whether a particular thing or activity qualifies, especially at the margins. And it is irrelevant that admiration doesn’t necessarily follow acknowledgment. For example, some might not consider Andy Warhol an artist, and even those who consider him an artist might not admire his work. Perhaps some don’t appreciate Monet or van Gogh. But art is not a popularity contest. Ultimately, it would seem humans collectively and broadly decide, even through an amorphous process of tacit acceptance, what is art by appreciating the thoughts, products, and acts that connect and communicate something of value beyond the most elemental necessities of life and the exigent moment. Even an inanimate object can depict something in the human condition and provoke an emotional response.

Art seems everywhere these days. It is on constant display physically and electronically. Acclaimed art is advertised and reproduced. It is on walls depicted in movies and television series. Museums court donors and visitors. Artists who weren’t appreciated in their lifetimes get their due belatedly.

Things were much different 15,000 years ago, when art appreciation must have been localized. Few beyond locals could see cave paintings or stone carvings. Most objects and implements adorned or decorated would have been appreciated only by those few in the family or band producing them. But clearly those humans appreciated visual representations as art, for conveying human values of admiration or gratitude.

Now art is widely advertised and exhibited. Art tourism is a thing.

Important exhibitions in San Francisco recently displayed an intriguing range of art by three masters. Their ostensible styles ranged from realism to abstraction; their media from gelatin photographic prints to painted canvas to bronze; their public recognition from broadly well-known to far-too-little known.

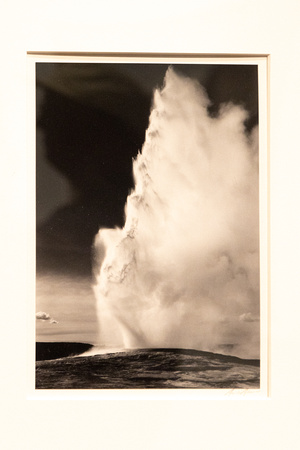

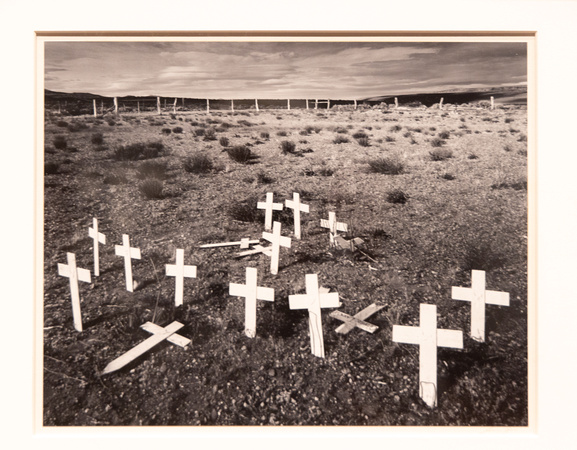

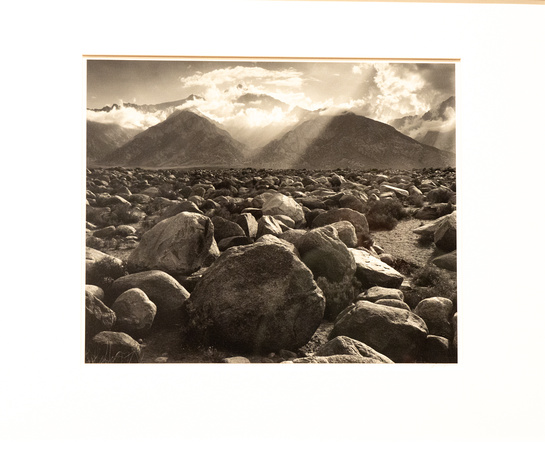

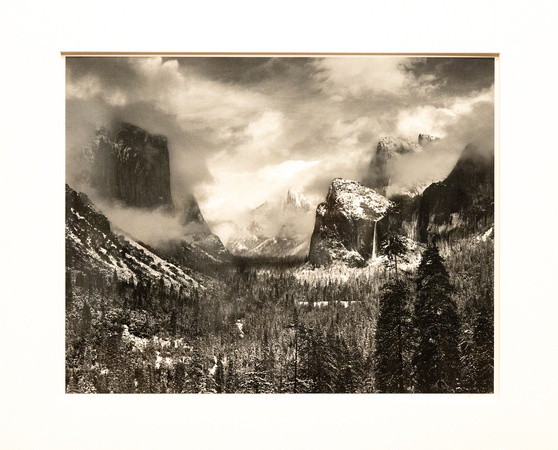

Ansel Adams, born in 1902, was the oldest of the three. But only he worked with the newest medium, photography. Adams was widely admired in his lifetime. His best work portrayed magnificent natural scenes — most famously Yosemite National Park. His rigorous technical approach to processing his negatives and printing from them produced some of the finest and most striking photographs ever made. His images are all about light. They are luminous. They explore the maximal tonal range (famously following his Zone System) of what his camera preserved on film, from light to dark. But his prints did not depict exactly what his large-format cameras saw or even what his eyes saw, because his mind had mentally translated what his eyes saw into the printed image he envisioned he would make. He used lens filters to heighten certain tones in his black-and-white negatives. He and skilled assistants printed to achieve the full range of tones he intended to produce. He inspected his negatives under a safe-light during development to get the density he wanted. He manipulated paper during printing, especially by dodging and burning, to alter tonal values. His exhibited prints were behind glass, making it hard to see the paper surface and texture and to photograph them without reflections, they nonetheless inspired. Their light, so to speak, shown through.

Adams’s style was ostensibly realistic. His images began with images of subjects, usually outdoor scenes, diffracted by camera lenses onto photographic film. Thus, in theory, what he produced was what the camera saw and would seem to be archetypical examples of realism. But it was an altered, filtered (optically and mentally) realism. What set his work apart from a mere mechanical, chemical, and technical exercise was how he interpreted what he saw, and how he made his finished product — his prints — depict his personal interpretation of the scenes before him. He manipulated strict realism. His real subject was light and how it affected the scenes he chose to photograph. (Not far from the Adams installation was a permanent de Young display, Three Gems, created by another manipulator of light, James Turrell.)

Perhaps because Adams was himself a product of San Francisco, the exhibition of his prints, at the de Young Museum in Golden Gate Park, was beyond well-attended: It was crowded with people who walked slowly and quietly from print to print, savoring each. Even assuming many were, like Adams himself, from the San Francisco area, not many photographers could attract such a large and reverential audience. Perhaps Stieglitz and Weston, or Lange or Avedon.

Here are some examples, three depicting natural scenes, and the other illuminating the crosses to signify the importance of the people buried there.